This is a temporary version of the project’s website.

Refugee Art: When Memory Becomes a Homeland

A true story of migration, survival, and art — connecting a family’s legacy to the creation of Exodus & Resilience.

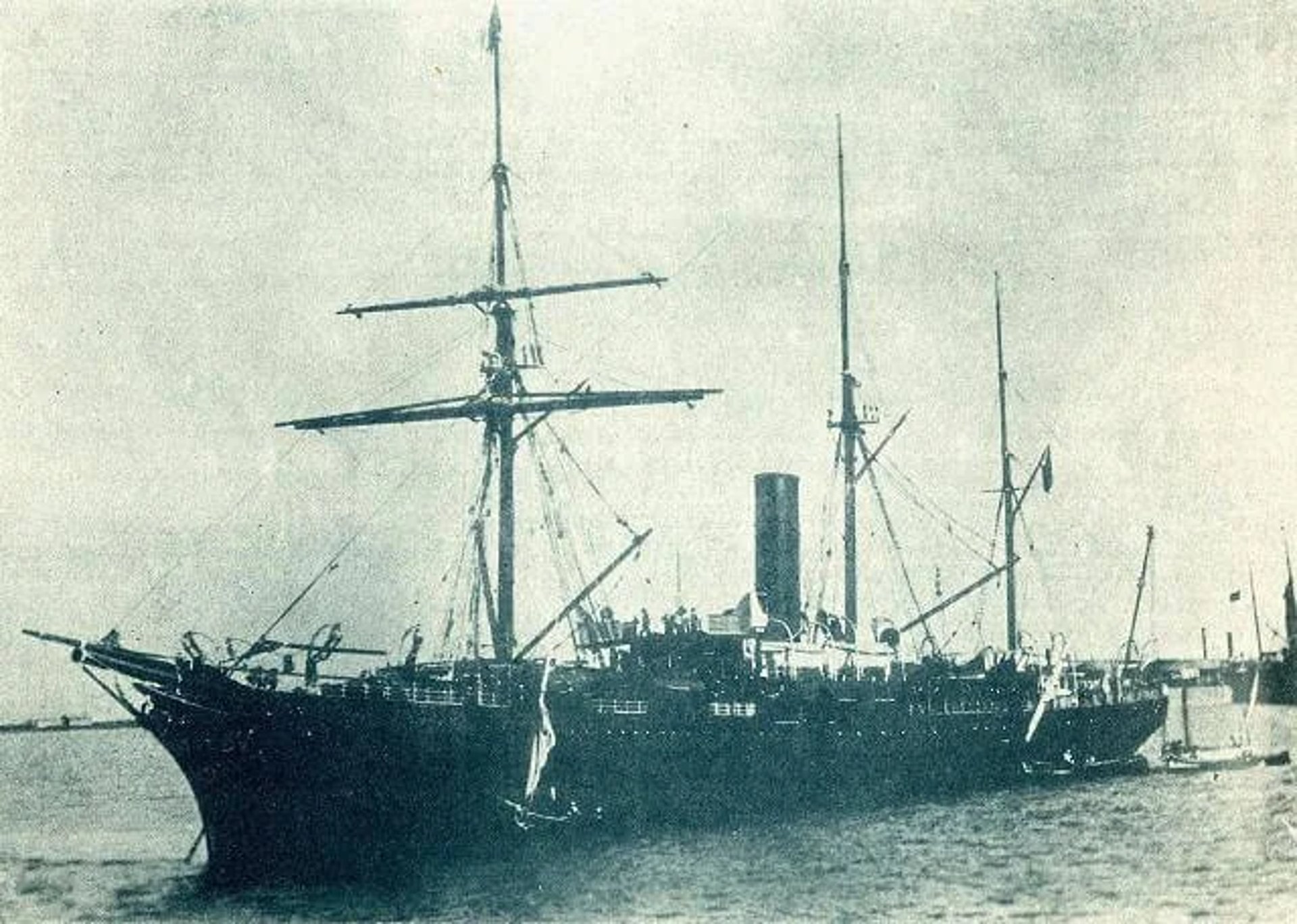

The steamship “Ciudad de Cádiz,” survivor of a Caribbean storm, 1921.

When the Spanish steamship Ciudad de Cádiz broke down in the Caribbean in October 1921, no one on board could imagine that from that wreck would emerge not only survivors — but a lineage.

One of them, a 25-year-old Venezuelan named Manuel María Ponte Machado, would never reach the port he expected. The ocean would rewrite his destiny.

A century later, his great-grandson would transform that shipwreck into a mission of memory, art, and empathy called Exodus & Resilience.

1. The Night the Ocean Stopped Breathing

On October 22, 1921, the Ciudad de Cádiz, a passenger steamer of the Compañía Trasatlántica Española, suffered a catastrophic boiler failure in Caribbean waters near the Lesser Antilles.

The ship, carrying about 150 passengers and crew, was en route from Cádiz to La Guaira, Venezuela.

Among them was a young Venezuelan man returning from Spain after finishing business and studies — a descendant of old Canary families whose history traced back to the conquest of the islands.

A sudden tropical storm struck that night. Rain hammered the deck. The ship’s lights flickered and went dark. Panic spread as the engine stalled and the vessel drifted helplessly in the current.

Then, through the chaos, another light appeared on the horizon.

The SS Monterrey, a Ward Line steamer traveling between New York and Veracruz, spotted the distress signals and came to their aid.

By dawn, all passengers had been rescued — no lives lost.

But the rescue ship sailed west, not south. Its destination was Tampico, Mexico, not Venezuela.

Fate had changed its course.

Sources: El Imparcial (Madrid), 25 Oct 1921; Lloyd’s List Maritime Archive; Ward Line Records, New York Maritime Museum.

2. The Port That Changed a Lineage

Tampico in the early 1920s was a boomtown of oil, salt, and hope. Mexican and foreign workers filled the docks; the air smelled of salt and gasoline.

Here, among the noise of cranes and steam, Manuel María met María de la Luz Loria Ortiz, daughter of a family of Spanish origin settled in the Gulf region.

Family oral history — preserved by his daughter, María de la Luz Ponte Loria — recalls the encounter as “a lightning strike amid chaos.”

He, the Venezuelan diverted by destiny; she, the Mexican whose eyes reflected the same sea that had just spared him.

They married around 1923, and in 1924 their daughter Elena Margarita Ponte Loria was born in Caracas.

The shipwreck that nearly ended a voyage had instead founded a transatlantic family that would connect Mexico, Venezuela, and Spain — and one day inspire a humanitarian project built on empathy.

Sources: Family oral history (Ponte Loria archives, Caracas, 1950s); Registro Civil de Caracas, 1924.

3. A Five-Century Thread

Manuel María’s story was not just a romance born of disaster; it was the survival of an ancient lineage.

His ancestors belonged to the House of Ponte, a Canary Island family whose founder Cristóbal de Ponte aided in the 15th-century conquest and settlement of Tenerife.

From that line emerged the Casa de la Quinta Roja and, later, ties to the Marquisate of La Quinta Roja (1691) and the Order of Alcántara.

One forebear, Esteban de Ponte y Blanco, was a Knight of Alcántara in the 18th century — his proof of nobility recorded in the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid.

Another ancestor, María Josepha Teresa Mijares de Solórzano y Tovar, descended from the first Marquis of Mijares, ennobled by King Charles II on August 19, 1691.

These were not titles of vanity, but traces of identity: evidence that across centuries, families carried their memory like cargo through war, exile, and sea.

Sources: AHN (Madrid) OM-CABALLEROS_ALCANTARA Exp. 97; CONSEJOS A.1691 Exp. 40; Guía Oficial de Grandezas 2025.

4. The Art of Survival

A hundred years later, that same current of displacement flows through millions of people.

But what was once a genealogical rescue has become an artistic and humanitarian one.

In 2025, artist and cultural founder Omar Bustillos Palis — Manuel María’s great-grandson — created Exodus & Resilience, a fiscal-sponsored nonprofit under Fractured Atlas (501c3).

Its mission: to document and dignify stories of forced migration through contemporary art, archival research, and education.

Every exhibition, tote bag, or mural becomes an act of remembrance — a way to turn inherited trauma into collective empathy.

The initiative connects artists from Venezuela, Lebanon, Ukraine, and beyond, echoing the same oceanic crossings that once carried their ancestors.

“Refugee art is not about pity,” Bustillos says. “It’s about continuity — about how memory itself becomes a homeland.”

5. Two Seas, One Purpose

The family’s parallel migrations — from Spain to Venezuela, from Lebanon to the Caribbean — converge into a single narrative: that survival can also be creative.

The Ponte lineage represents the endurance of heritage; the Palis-Saud line, the resilience of refugees from the French-occupied Levant.

Together, they illustrate how nobility and necessity, privilege and exile, coexist within the same bloodline — and within humanity itself.

This convergence now lives in Exodus & Resilience’s collections and digital archives, where artworks and genealogies meet under one premise:

the art of remembering is itself a form of refuge.

6. The Mission Beyond Titles

While legal rehabilitation of historical titles proceeds through Spain’s Ministerio de Justicia, the real purpose is pedagogical:

to demonstrate that any family can reconstruct its past, retrieve its documents, and claim dignity through knowledge.

In workshops and exhibitions, the project teaches others how to access archives, preserve stories, and link them to global themes of migration and belonging.

Because recovering one’s history is not an act of pride — it is an act of healing.

7. Reflection: The Sea Does Not Divide Us

When the Ciudad de Cádiz drifted silent that October night in 1921, the sea seemed endless.

But from that uncertainty came new life, marriages, children, migrations — and a mission.

The sea does not divide. The sea connects.

And sometimes, a shipwreck saves more than lives; it saves lineages, identities, and futures.

Sources & References

El Imparcial (Madrid), 25 Oct 1921, Hemeroteca Digital BNE.

Lloyd’s List Maritime Accident Registry, 1921.

Ward Line Shipping Records, New York Maritime Museum.

Archivo Histórico Nacional (España), OM-CABALLEROS_ALCANTARA Exp. 97; CONSEJOS A.1691 Exp. 40.

Geneanet database (Manuel María Ponte Machado 1895-?).

Guía Oficial de Grandezas y Títulos del Reino, 2025 (Ministerio de Justicia de España).

Fractured Atlas 501(c)(3) Fiscal Sponsorship Agreement, 2025.

Oral history recorded by María de la Luz Ponte Loria, Caracas (1950-1980).

Historical Archive – 1921, Hamburg-Amerika Linie

Connect

Join us in shaping stories that matter.

info@exodusimpact.org

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Exodus & Resilience and Exodus Impact are independent but interconnected initiatives founded by Omar Bustillos.

Each operates under its own legal and fiscal structure — Exodus & Resilience through Fractured Atlas / By Sibarita LLC; Exodus Impact seeking TIDES / Intercontinental Art LLC (in process). — within one common vision: To turn empathy into legacy.

A full professional version will launch with the resources generated by the initiative.